|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Extreme Makeover, Global Edition, Production Episode 2 |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | |

| Aug/04/2006 | |

|

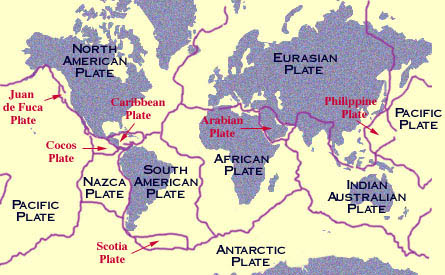

When in the course of human events things get really messed up, well, then, it’s time to rethink some basic concepts...Neoclassical economics cannot explain how a national economic system, much less a global one, will operate in the long-term, across industries, in the presence of technological innovation, and in conjunction with the ecosystems on which all economies depend. When in the course of human events things get really messed up, well, then, it’s time to rethink some basic concepts. In last month’s column, I proposed that a new kind of global political and economic architecture needs to be envisioned, or else the reigning neoimperial philosophy and its beneficiaries, the global elites, are going to run the global economy and biosphere into the ground. The first principle of such a global makeover is that the natural

boundaries of an economy are the physical boundaries that the

movements of tectonic plates have bequeathed to us, the continents

and subcontinents such as India and China.[1] This concept is in direct

conflict with the reigning sales pitch of economics, that

globalization leads to the best of all possible worlds because

production and the market are global processes, not continental

ones. In reality, extreme globalization would produce much less

global growth, with much worse distribution of wealth, than a

continentally-based global economy.

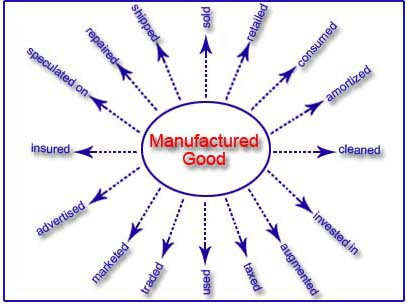

In the service of manufacturingThe second principle of an alternative global architecture is that production of goods and services, and in particular, the production of manufactured goods, is at the center of the economic universe. Policy should be production-centered, not market-centered. The rest of the economy depends on manufacturing in general and in particular on the machinery industries.

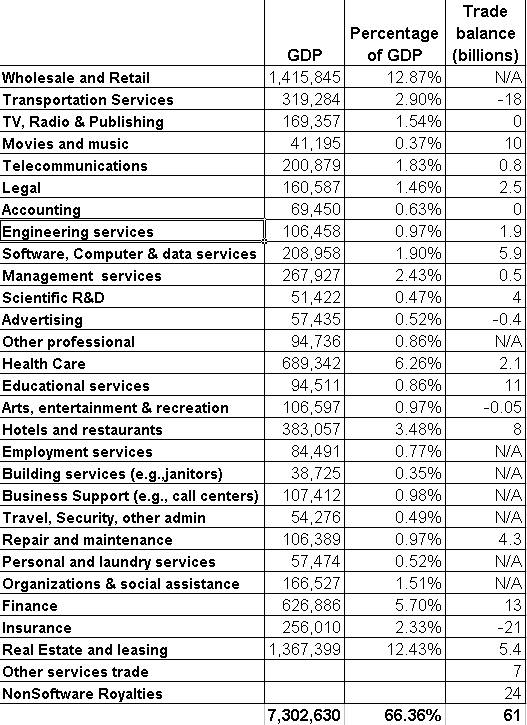

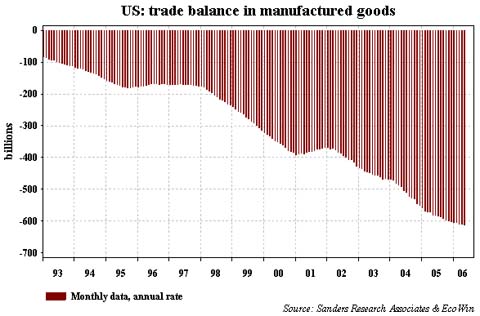

Looking under the hoodThe U.S. economy, that bold pioneer of the post-industrial future, is just as dependent on manufactured goods as any other society. The following table shows the percentage of the economy that each subsector of the service economy provides in the U.S., as well as the trade surplus or deficit of each:

Table of Services in U.S. economy, 2003, Value-added [5]Notice the sheer diversity of services, which constitutes fully

two-thirds of American economic activity. Also notice that the trade

surplus of $61 billion is tiny compared to the trade deficit of

manufacturing of the U.S., hurtling toward $1 trillion per year.

Engineering services shouldn’t be considered a service because

engineers are at the center of the manufacturing process. Scientific

R&D requires some of the most sophisticated equipment on the

planet. Engineering and scientific education requires great amounts

of equipment in order to create people who can make even better

equipment, which in turn is used to produce most of the progress in

the service economy – think of the impact of the internet, which was

made possible by advances in semiconductor-making equipment. Nevermind all that, just make me a star!

But what about that part of the economy that looms so large in

the imagination of the masses, the sector that includes all media

such as TV, radio, and print, and entertainment such as movies,

music, theater, sports, arts, and gambling? What percentage of the

economy do these comprise? When I asked classrooms of advanced

seniors in high school this question, the answers ranged from a low

of 10% to a high of 50%. The answer is -- 3%. These industries

dominate the society’s culture and are used for political

indoctrination – and even, occasionally, to enlighten -- but they

are fairly insignificant economically. At least in the United

States, I would bet that more young people dream of succeeding in

these industries than all the other economic sectors combined. But

such ambitions do not help the economy in the long run, because an

economy needs people who want to make the machinery that makes

goods, a geeky occupation if ever there was one. What’s trade got to do with it?Production is not spontaneously generated by the market. According to one writer, “From the time of the ancient Romans, through the Middle Ages, and until the late nineteenth century, it was generally accepted that some life forms arose spontaneously from non-living matter”.[6] The lack of interest in production in neoclassical economics gives rise to a similar logic vis-à-vis production and the market; all one needs to do, allegedly, is set up the conditions of a perfect market and, voila!, new technology and better production techniques will come pouring into the economy. History is not kind to such preconceptions. If the Romans had had a perfect market system, their economy would not have been significantly larger. If they had had our production technology and their market, their economy would have experienced explosive growth, albeit with certain inefficiencies caused by a primitive market. In his classic study of the Trobriander Islanders, the anthropologist Malinowski described a “primitive” people with a very sophisticated, albeit Stone Age, system of exchange; a modern industrial system was not therefore spontaneously generated.[7] The Soviets, with a very flawed system of exchange, still became a superpower because of their technologies of production. No technology, no wealth. Bad market, less wealth. If economies are based on continents and on manufacturing, then

what function does trade serve? Free trade is critical

within a continental manufacturing economy because the

various stages of production need unfinished, intermediate goods to

be moved from one part of the economy to the other. But trade

among continental economies is not very important, as long as

each economy has done the right thing and constructed its own

complete suite of industries.

Not only does a relatively scarce material make trade necessary,

but scarcity leads to geopolitical jockeying and eventually to wars.

The conventional wisdom since before WWI was that trade would lead

to greater peace because trade produces gains for all parties.[9] Perhaps this is true when

a cessation of trade would not be catastrophic, but when the traded

commodity is absolutely critical then control of trade actually

becomes a cause of war , not of peace. The Bush neoimperial

campaign for control of the global oil trade is the premier example.

Solar energy generation, by contrast, is most dependent on silicon,

which is the second most plentiful mineral on the planet. A global

reliance on solar energy as opposed to oil would remove a major

cause of war. When something has to be traded, somebody

thereby gains power, and great harm is usually the result. Let 100 technologies bloomWhile trade can be important because of the unequal distribution of raw materials, interregional trade can actually be helpful to humanity by spreading innovations from continent to continent, as it has for millennia.[10] That is, if there were nine fully functioning, thriving industrial centers in the world, then there would be nine sources of first-rate technological innovation. Certainly this would be better than having two or three, as presently. Unlike the theory of comparative advantage, which absurdly advances the idea that it would be better for humanity if each industry specialized within one nation, the history of technology shows that having many centers of innovation encourages more and better innovations.

Darwin’s theory of evolution rests on the concept of multiple centers of innovation. In the case of evolution, each reproducing organism is a center of innovation, because each reproduced organism may constitute a “variation”, to use Darwin’s term, from the original from which it was born. It is the set of variations which gives rise to the ability of life to adapt to changing environments, because some variations do better than others in a particular environment. If life had followed the law of comparative advantage, we would probably all be sea slime, because all of life’s eggs would have been confined to one basket. As Mao said, let one hundred flowers bloom – only don’t do as Mao actually did, which was to eliminate those he didn’t like. Mao invented a great metaphor, but the irony is that this concept is part of the core of mainstream economic thinking. After all, one of the main benefits of a competitive economy is supposed to be the capability of the each firm to outcompete the other by developing a better way to make something. The theory of comparative advantage contradicts this idea by advancing the notion that monopolistic specialization will lead to a better global economy. A world based on globalization would be less technologically active than one based on production-centered, continental economies, because regional economies would create more innovations than one in which each specialty was monopolized by one region. Every region, even the U.S., needs to have a manufacturing system in order to be wealthy. What, me worry?Currently, American economists are facing an ideological dilemma. The United States is running up huge trade deficits in manufactured goods, because the manufacturing base of the country is failing. Even the pied pipers of the Federal Reserve Bank acknowledge that such trade deficits are “unsustainable”.[11] Since manufactured goods constitute most of world trade, and the U.S. economy is becoming more and more based on services, the U.S. is more and more unable to exchange goods for goods. The implication of this situation is clear: in order to be wealthy, the U.S. must rebuild its manufacturing sector. But to admit that one sector, manufacturing, is necessary and irreplaceable, would be to throw the profession of economics into chaos.

All of the tools of the economist’s trade are based on the ideas of substitutability, sets of linear equations, equivalency to mechanical systems such as gases and liquids, with all of the attendant virtuoso mathematical manipulation. To admit that there needs to be a permanent sphere of manufacturing and machinery at the center of the economic system, surrounded by other, irreplaceable sectors, all with specific relationships to each other, would imply that an entirely new way of looking at the economy was in order. So economists tend to stick their collective heads in the sand in ignore the looming economic crisis. The principle that manufacturing is a necessary and central part of the economy logically leads to the conclusion that if manufacturing is in decline, then it is necessary to reverse that decline. In the case of the U.S. the decline of the manufacturing base has been caused by the relatively unregulated operation of the market and the construction of a huge military-industrial complex. Therefore, the only possible way to rectify the situation is to have the government intervene in the economy by redirecting resources from the military to the manufacturing sector. Enter government, stage leftAs inconvenient as the truth of the centrality of manufacturing may be, an extreme makeover of the global economy would have to include a reorienting of the public’s focus from markets to production. And much to the consternation of those who are profiting from the decline of American manufacturing, the third principle of a global economic architecture should be the following: government must manage the economy in order to support manufacturing, because the market cannot do the job. Neoclassical micro economic theory is actually a theory of how an industry, made up of a homogenous and fairly numerous set of firms, will behave in the short term. The theory does not explain how industries interact with each other to form a system, how firms take over whole industries, or how technological innovation changes the dynamics of the economy over the long-run. Neoclassical macro economic theory, at best, is a theory of how an economy will operate, in the aggregate, over the medium term. Neoclassical economics cannot explain how a national economic system, much less a global one, will operate in the long -term, across industries, in the presence of technological innovation, and in conjunction with the ecosystems on which all economies depend. The long-term, global processes of the economy are inherently chaotic. That is, small causes may have large effects, random elements may change stable trends, there may be “tipping points” that shift a system from one fairly stable mode to another, and technological change is unpredictable. In an unpredictable world, only the government has the capability of managing an economic system as a whole. This doesn’t mean that the government should centrally plan the economy, Soviet-style – quite the contrary, it is because of the chaotic nature of economic and ecological systems that central planning cannot work.

Government has been pursuing this stewardship model with regard to ecosystems for sometime, particularly within national parks like Yellowstone. If deer are getting out of control and eating all the grasses, reintroduce wolves. If a species is in danger of being eliminated, protect it. If there hasn’t been a fire for a long time, prevent an “unnaturally” destructive fire by burning the underbrush. In a similar way, governments have been managing economies since civilization began. The main method governments use to manage the economy is by controlling the infrastructure -- the transportation, energy, communications, and water systems of an economy. Governments have also encouraged production throughout history, in the industrial age by creating a manufacturing sector if necessary, or by protecting “infant industries” from larger, more advanced ones, as advocated by Alexander Hamilton. Governments have also been intimately involved with the education and training of the population, and except for the U.S., insuring the health of all of its citizens. Because governments were presumed to be so important in the management of the economy, economics was originally labeled “political economy”. If manufacturing is central and necessary, then government stewardship is also necessary, and we can put the word “political” back into “economy”. But if governments need to manage the economy, who will manage the managers? Political power is best seen as beset by positive feedback loops. The more power one has, the more power can be usurped. Such snowballing of power eventually leads to a weakened economy, because the unchained beast of government sucks all of the resources out of the economy, lavishing riches on government elites, their friends, or in an attempt to extend power beyond national borders, on a voracious military. The best solution to this threat so far devised is to implement democracy. But what kind of democracy? And is democracy at the national level good enough? Is there a way to extend democracy to the economic system? What about at the global level where so many problems must be solved? How can we solve the problems of global warming and global economic financial meltdowns?How will it all turn out? In what political and economic directions are the continents moving now, and what hope is there for…the future? Find out in the heart pounding, season ending episode of…Extreme Makeover, global edition! You can contact Jon Rynn directly on his jonrynn.blogspot.com .

You can also find old blog entries and longer articles at

economicreconstruction.com. Please feel free to reach him at

This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need

Javascript enabled to view it

. Notes[1] See “Extreme Makeover, Global Edition, Episode 1 ”. [2] The best of the liberal mainstream economists in this regard in Dani Rodrik at Harvard. [3] These ideas are elaborated in “Why manufacturing and infrastructure are central to the economy ”. [4] WTO publication, . International Trade Statistics , 2004, World Trade in 2003, Overview , page 23, Table 1.9. [5] Percentages are from Survey of Current Business, January 2005, .Annual Industry Accounts.,Table 1, and trade figures are from Survey of Current Business, October 2004, .U.S. InternationalServices., Table 1. In order to calculate the value-added percentages for several small servicesubsectors, I used the data on revenue to calculate the percentage that a certain sub-subsector was of a subsector, and applied that percentage to the subsector.s value-added. [8] This idea is further elaborated in “Extreme Makeover, Global Edition, Episode 1 ”. [9] The Princeton political scientist Michael W. Doyle has written extensively about this idea. [10] The economist Amartya Sen has written on this topic as a challenge to Samuel Huntington’s theory that civilizations clash. [11] See, for instance, the Captain of pied pipers, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, in a speech given in 2005. |

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|